she doesn't know me yet

belated grief for a love that came too early: my mother knew how to love me long before life betrayed her.

“the nature of time in the country of trauma is always present continuous,” says Ankita Shah. grief, if we turned it inside out, might also be seen as an endless, permanent waiting—by contrast to the end that triggered it. to miss someone, to grieve, to live among ghosts—perhaps it’s all another way of saying, I’m still here, “I’m still waiting” (Ankita Shah, why we need grief memoirs). maybe losing someone, suffering for someone, always happens in that tense and mode: present and continuous. it’s now, but the now doesn’t end. it’s now, but it stretches on. it’s the present, but it’s also the future—because the present creeps forward and swallows whatever lies ahead, until everything is the same, all caught in its belly. it’s always present tense and this present, this now, is long and drags, maybe not only because of its continuous nature, but also because of its lateness. for me, at least, grief always arrives late. it’s delayed, postponed, lagging. the moment, the hour, the place—none of them are the same anymore. time has gone on, looped, twisted back around. and yet, there it is. grief shows up late. after hours, after us. but so does love.

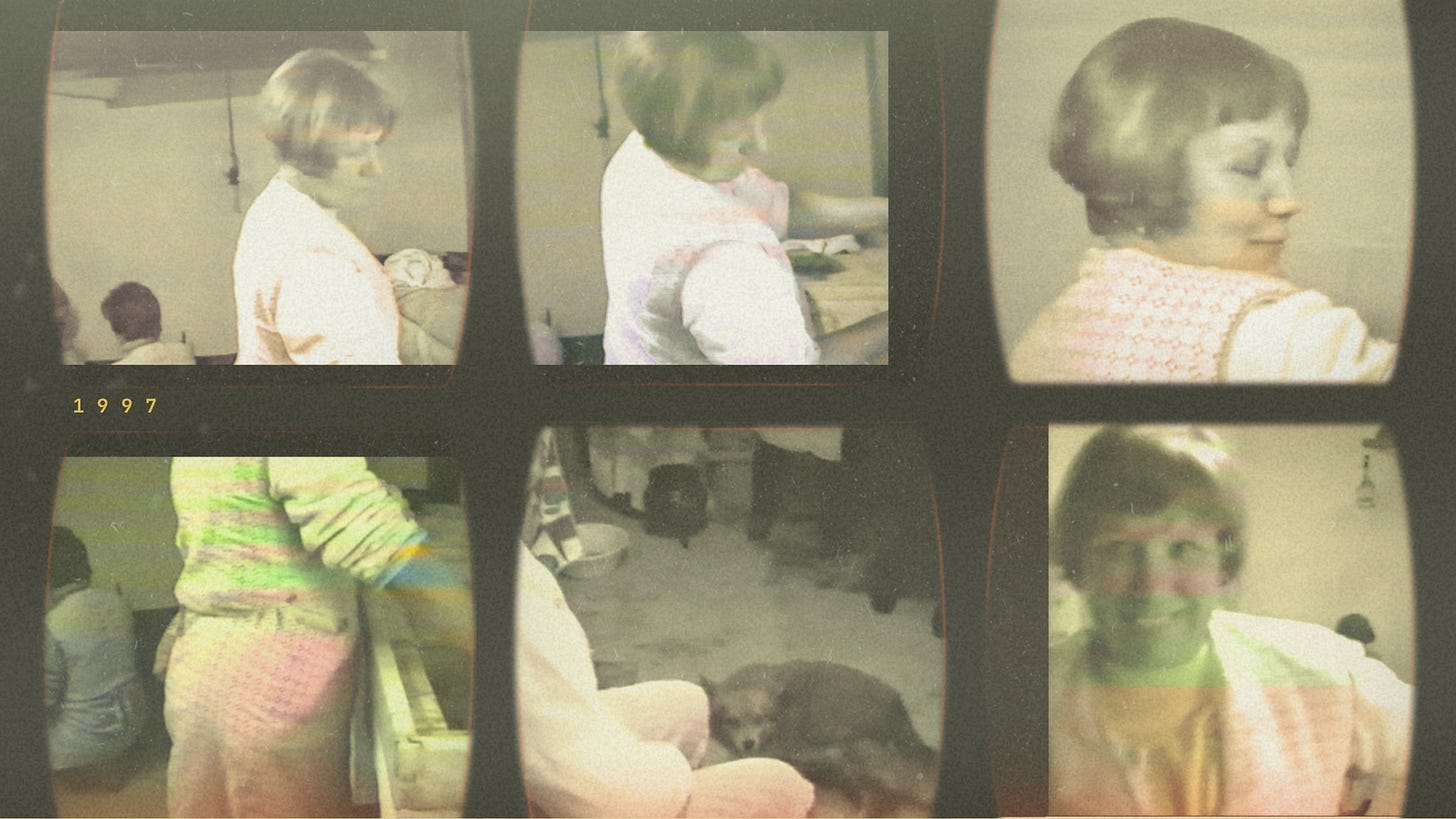

I see her, we all do. a woman wearing a thick baby-pink wool sweater. her light hair is cut in a blunt bob, just above the shoulders. the camera—someone is filming continuously—zooms in and out, but no one speaks directly to her. no one plays a part, at least not consciously. they’re in a kitchen—a stone kitchen: stone floor, stone walls, stone counters, though the counters are topped with a layer of white marble, with grey and black streaks that seem like dark veins, you could say. if we tried to read what those veins said, they’d say nothing, at least not to most of us. but some women, my aunts, would shake their heads violently and say, ‘they do say something’. they will tell you that they can be read, like the palm of a hand. those veins seem to belong to enormous hands—hands bigger than the kitchen, bigger than the stone; that’s why we only see the lines. it’s as if someone had also zoomed into the counter, until only the vessels remained in sight. the grey or black streaks they can read are as dried blood or dark blood, they say. they mean something, at least to those who can see it. some of those women are in this kitchen now.

it’s a working kitchen—aside from the stone, there’s wood: long wooden benches and the big wooden table, logs stacked in a corner for the fire, the wood-burning stove. a kitchen stripped of decorations. later, it would become the kitchen of Christmas lunches, of Sunday roasts, of birthday parties for children not yet born at the time of this movie—then, there was only one child, and he doesn’t appear in the scene. there are three women in the kitchen—besides the one we first saw, who is still in the foreground, and has not turned towards the camera yet. she’s clearly the youngest of them all, though she has a tall, strong neck and hands that look like they could hold everything. hands covered in gold rings—one with a black stone, maybe onyx or obsidian. the rings catch the light that enters the room. some light flickers and seems to die between her fingers, tiny supernovas falling on her skin. every so often, the light hits the camera lens and hovers between those in the image and the one who is filming, and status there, between them, like a thin, lacy veil, like the wings of a fly, like glitter trembling in the air before vanishing.

the other three women crouch or sit on stools so low they seem to be sitting on the floor. they lean over big round basins, filled with pork and chicken entrails, with meat from other animals. they’re making smoked sausages (‘enchidos’ is the original word, and the one that does it justice) filling them by hand. once ready, they’re handed to a man in the room, who does the final touches and hangs them above the fire. they do this every year. we’re in northern inland Portugal, in a place where slaughtering, cleaning, kneading and stuffing sausages is a tradition, at least in the villages. we’re not in a village now, but that’s where the older women in the room come from, every year without fail, to bend low to the kitchen floor and begin the labour.

the woman we first saw isn’t working with the meat—she’s doing other tasks: washing dishes, clearing the table, rinsing out the basins once they’ve been emptied of guts. suddenly, someone calls to her—a man’s voice, from behind the camera—and she turns, almost surprised. her hair sways lightly, weightless, as if it were no denser than the rays of sun dancing on her rings. her eyes are green, with lines drawn in a light grey. she has bangs too—short and straight, which surprises those watching now: “I didn’t know she wore bangs!”

she smiles once or twice—a smile that no one has seen before, and maybe no one will never catch again. it’s warm, young and almost intoxicated. slightly exaggerated, overflowing with feeling, like the kind of smile that escapes us on a summer night, when the body melts and expands, and we feel infinite. it’s the smile of a woman, a teenager in love. maybe even of a child. the person behind the camera asks her to say something. she shrinks back into herself, shy, embarrassed. one hand lifts to brush off the silly request. that innocence and that shame are also both dated, stored away. they belong to those times. she never seemed shy and so innocent again in all the years that were to come. her round cheeks turn red, full, like ripe, shining nectarines. as the woman only smiles, and the silence lingers, the camera zooms out again. only then do we see the woman’s half-body in frame.

in the room where we’re watching the film, there’s a sharp, surprised breath from someone, ah! yes, sure she looked a bit different, with fuller features, a rounder face, but only now do we see that she is pregnant—and it looks like pregnancy has filled her completely, become all of her. not in a diminishing way; she’s not just a pregnant woman, although that’s already so much. it’s more like nothing else matters – her expecting, her smile, her contained happiness, the baby on her belly, have an overwhelming effect on the whole scene, on everyone watching it.

the camera trembles again, focuses on her belly. shortly after, she sits down, tired. her ankles are swollen—her legs, arms, face too. it’s a high-risk pregnancy; that’s where the swelling comes from. she rests her hands on her belly, over a plaid apron worn atop the pink sweater. on her feet, are wool socks in a darker shade of pink. it must’ve been cold. it was maybe December. if so, the baby would be coming soon—though they wouldn’t know that yet. she moves through the kitchen as if she carries no weight at all, as if every gesture was rehearsed, always landing just right. a touch to the face that isn’t a rub, a pass through her hair that leaves it untouched, like fingers gliding through water. she is visibly heavy and exhausted, but takes light steps from here to there, like dancing, as if nothing hurt. back then, she and the man behind the camera, her husband, still believed they’d have a March baby—not a premature one, coming in January. it was 1994, and those hands still knew nothing of what was laying ahead.

the scene flickers, dissolves, vanishes. when the image returns, we don’t come back to the same place, the story doesn’t pick up. we never see, at least in that film, the baby, the parents. we never see the sausages being finished.

that woman in 1994 was my mother, yes. it was winter, and she was at my paternal grandparents’ house. she was about 35, and I was inside her belly. my father was behind the camera. there’s a hum on the TV—the static buzz of a thirty-year-old film—and time fixes itself once more in her image, on her shy smile, on her silence.

but I don’t know that woman. the one standing still, waiting. I don’t think she knows what’s ahead, either. still in life, still in the film—it’s nearly the same. it feels like I could step forward and ask her everything, though I don’t even know what I would ask, but it seems I could, if I wanted. but not really — I can’t. I try, but her green eyes stop looking at the camera, turn toward me—and, across the screen, they don’t recognise me. I can see that she doesn’t know me. she doesn’t know her yet—the child staring back at her; they don’t even share the same eyes, the child’s are brown, though they do share the same hair— in cut and colour. this child means nothing to her yet. no one’s told her. no one could tell her; how do you talk about what hasn’t happened yet? what hasn’t happened has no image; that’s why we can’t, as much as we try, imagine ourselves dead—we don’t know how it looks like.

if people around them could, maybe they’d shout, that’s Carolina! that’s your daughter! but the image is finished, they cannot say anything more than was already said back then. perhaps, even if they told her, she would be confused – maybe she was not yet 100% certain yet that she would give me that name. maybe she thought she had time to choose.

this woman who will become my mother looks like an actress in a film that she herself doesn’t know how it ends; trapped in her last line, her final gesture. she’s done everything as they told her, so far. now, expectant, she waits for her cue. I feel an urge to press matches to the screen—maybe the flickering light will illuminate something more, hold the image still when everything else goes dark. I want to lean in and ask:

‘do you know I’ll have a nose like yours? it’ll start small, but then turn out just like yours—which is almost like dad’s—but with that little bump that you and godfather have’. I want to ask: ‘later, when I ask you about that pink sweater, will you remember it? or will you say you never wore pink? do you know what’s going to happen? do you know you’ll suffer terribly because of me, be rushed to the hospital, and we’ll fight to figure out if both of us can exist simultaneously? dad will have to write down, in a horrid form they’ll give him, who stays, in case something goes wrong, and it turns out we can’t live together in this world. do you know we’ll both make it—but for a long time, neither of us will understand how or why?’ maybe we’ll have to call the doctors from that day and ask if there was any umbilical cord connecting us. they’ll look at us like we’re mad. ‘of course there was one, how could there not be?’ and we’ll answer: ‘it doesn’t feel like there was’.

‘if there hadn’t been, there wouldn’t be a baby’, they’ll say, ‘don’t you remember us cutting it?’, they’ll add, asking you. and you’ll reply, lips pressed together: ‘no, I don’t remember. I don’t know if there was anything to cut.’ silence. the room is warm. the water in front of us too. it looks thicker, like blood without colour. ‘and what if it was there but was cut too soon?’, I ask now, but no one answers.

‘there are other tapes—you could put them on!’, someone in the room, where we have been watching the film, says. or maybe I tell myself. ‘I know. I know.’ but I don’t want to – I want to see this one, again. maybe I need to reassure the woman on the screen, tell her that I am not only thinking about the sad things that are yet to come. I can recall good moments too, you know?

you don’t know it yet, but before I ever say aloud that I don’t think you like me anymore, I’ll already have realised that other people don’t like me that much either—not the kids at the new school, anyway. in that new world, there will be established groups and insults to anyone outside them. they’ll say my clothes and boots aren’t the right kind. they are not fashionable. did you know they weren’t the right kind? I didn’t know, but I’m sure you didn’t, either. I believe you. it’ll be hard for me to accept that you and dad aren’t the ones who know best anymore, and that other kids will tell me how I should be, what I should wear. you told me the skirt was pretty, and I thought that too, so how could I imagine that some horrible girls at school would knock me to the ground and pull my hair because of it? I couldn’t, neither could you. I don’t blame you for any of it, you know. the skirt was pretty, and you wanted me to feel pretty. and despite the sad things I said before, I will remember damn well the moments you protected me. one day, I will come home after school and tell you I don’t have any friends, that they mock my backpack because it’s outdated, and you’ll take me to that stationery shop in town and let me pick my favourite. It’ll be a Harry Potter trolley bag, and it’ll make me so, so happy—until I find out they don’t like me with that either, that is ugly and childish, and they’ll push me until I fall.

don’t worry. you couldn’t have known.

one day, you and dad will search the entire city with me to find a Tamagotchi— after I cried that everyone else had one except me. at some point, I will give up (we visited so many shops, I honestly don’t know how you and dad had the patience), and start crying in the car, and you’ll go to one last store, find one, a yellow one, and buy it for me. I still don’t know how you were able to find it. I remember I called it Alex.

there are good memories. there will be wonderful films yet to come. when I grow up, and reach the age that you have now, in this film (more or less), I will go through some of my worst mental health moments, and you’ll cry when you see me cry, and you’ll put two soft duvets on my bed so I can bury myself in them (for months, I will only be able to sleep with them). you’ll ask me to paint little stained-glass panels, or make ceramic vases and plates, for you to display in the living room that had once been untouchable. you’ll let me sleep without opening the blinds or yelling at me. you’ll make me my favourite cake (bolo de bolacha, I don’t know how to translate it). one day, after a moment of courage, you’ll tell me, I could only do it because I could hear my Carolina’s voice in my head.

I’ll watch other tapes—from the days when you still wore those rings and that smile. I’ll see how you held my tiny hands to teach me how to walk. I know you’ll hug me, I know you’ll pick me up and say, ‘look, it’s daddy!’ — daddy, almost always behind the camera – and I’ll burst out laughing. we’ll take photos where I hold on to you so tightly, I clench my teeth, and you hold me back, calm, dressed in yellow—almost always in yellow—while also holding my favourite stuffed toy from then, that dog with the red collar.

and still—why am I so drawn to this video, this image, always?

because there is no other like it, maybe? one day, those rings that shine and scatter golden light across her skin, will be gone. there will still be fingers, of course, but bare ones; the rings had already been violently cut off with pliers, left on a hospital bed or in a plastic bag, torn from swollen hands.

but for now, this woman turns to the camera and smiles, shyly. watching her makes me dizzy, weak, haunted. I feel I’m out of time – like I arrived too late to the party, though someone whispers, ‘there is no party’. ‘then what are these balloons?’, I ask. ‘the party’s over, a long time ago’, they shrug, and disappear.

I look at that woman, and I know the love she bursts with was directed at me. I stretch my hands out in hope I could catch it, clutch it tight, bottle it before it escapes. I have no idea if I’ll manage to hold it, I don’t know how it could feel if it ever touched my skin: would it have texture? would it be solid? would it be just a glimpse, a spectre of something? one day, I’ll think I’ve captured a bit in a jar. but no. that love belonged to another time, another space. it was love at its purest form, before touching the world, before being tested, battered, worn thin by it.

you look at me, at the camera, still, and I know — it hasn’t happened yet. you haven’t yet been touched by what will change everything. maybe this is one of the last moments before the world folds in on itself and nothing is ever the same again. it’s like the turning of the year, of the century, the millennium, it’s that fragment of life before the moment the whole world will one day call the moment everything changed.

soon, I will be born, and I will never have known that woman from back then, who is now my mother. I want to ask — ‘do you know what’s coming? do you know that at ten years old, I’ll write in my diary that I don’t think you love me anymore?’

I’ll read it to you,

“I’m sad […] it was so good when I was little. she’d stroke my hair, I’d get into bed with her, all warm and safe, and smell her cream, and she was sweet to me. now nothing’s like that […] I wish everything could go back to how it was, and I could become that child again, waiting in my parents’ bed for the sleep butterfly to come.”

‘do you know your mother – my grandmother — will become crueller? to me, to you? do you know that we’ll lose grandpa Armando? that you’ll feel alone? that dad will leave home? that you’ll realize there’s no such thing as eternally happy marriages?’

sorry, I am being mean; I honestly don’t want to tell you any of this, you don’t deserve it. but for a moment I feel that maybe if I say it, you will take a step back, change something in the story, erase the script, return to that smile and that pink sweet sweater. who knows? please?

‘do you know we’ll fight and hate each other and cry and go years without speaking on the phone?’ that this silence will last until the day you—while I’m walking the Camino de Santiago with one of my best friends—call me to ask how it’s going, and I’ll answer, ‘I’m nearly at Valença’, and that my friend—by then, a decade-long friend—will say, ‘that was the first time I ever heard you talk to your mom’.

‘do you know that one day, in 2008, an ambulance will stop outside our gate, and you’ll be lying in the bathroom, and dad—before I scream for him—will be taking care of the garden he loved so much?’ it’ll be Mother's Day, May 4th. it’ll all happen, and I won’t fully understand, not then, not for a long time. maybe I’ll never understand. some people will try to help me to do so — a therapist, the first one I’ll ever tell this story, will bend forward in his chair, elbows on knees, and ask me if I realize how serious it has been. by then, I’ll already understand better, but not entirely. maybe I’ll never want to fully understand. because maybe all I wish is I could erase those years of rupture and pain, and pretend they didn’t happen at all.

but they will happen. I will be an angry teenager who hates herself, and I will write on my diary, again, ‘shouldn’t she love me unconditionally?’

but maybe this is also the right time to tell you that I’ll write it many times in my journal (not in the ones you read — those were the angry teenage ones, but the in earlier ones), ‘I miss my mother. I miss the way she used to be.’

‘do you know you’re my mother? you will be my mother.’

there will be many other beautiful moments. and sad moments among those beautiful ones. you’ll sign me up for art class, but will make me sign my work with the name you want, your surname, not dad’s. one day, in a moment of trust and innocence, I’ll tell you about the boy I liked, only for you to call an emergency meeting at school to end it because I was ruining my life. (it’ll be the first and last time I confided something like that in you.) you’ll agree with dad when we decide I can leave the university dorms and share a flat with friends, but when the day comes, you’ll sit at the dining room table while I cry in my new room alone because you refused to help me with the bed, or buy me curtains, a duvet, a lamp.

I’ll tell you another thing: people will often ask me why I keep trying. why I try to hold the family together. how I manage. I’ll want to answer, there’s no other way to live. I have to try.

we’re in different times — she in the past, I am in the present. maybe it could never have been any other way. some things, like grief and love, always arrive late, later than you’d expect. the time delay can last months, years, lifetimes. for me, it took me watching that video to feel a love I had never seen but suddenly felt. it took waiting to grieve something I never knew, but now I’m certain that had once existed.

that’s why we try. why we go on. why we pour alcohol on the wounds, stitch them shut when they tear open again—just to see if we can still reach each other. she’s still there, in the film, smiling, untouched by all the years to come. her hand can still reach out, and if she stretches her fingers, she’ll still feel the warmth of the room, her husband’s arm, the faint smoke of whatever is cooking behind her. she’s a star waiting for a lifetime of light. ‘I deserve it’, she thinks. and she’s right – she does. but she doesn’t yet know that, sadly, deserving it won’t be enough.

and that— I don’t tell her.

I’ll be so happy, I read in her eyes. and I don’t have the courage to say, you’ll be so sad, mostly sad. one day she won’t wear rings. not her wedding band, not any of them; they had to be cut off. her hands will rest on the table, swollen in a different way — tired, worn, cracked.

and still — in that second, as she turns her back, looking away from the camera, I manage to whisper to her, to this woman who doesn’t know me yet, you’re my mother. she doesn’t turn around, the image trembles, the film ends, the screen shuts off with an electric click, and everything goes dark.

but it was my mother; it is my mother.

extra:

I see them standing […]

I see my father strolling out

under the ochre sandstone arch, the red tiles glinting like bent

plates of blood behind his head, i see my mother

with a few light books at her hip, standing at the pillar made of tiny bricks,

the wrought-iron gate still open behind her, its sword-tips aglow in the may air,[…] they are about to get married,

they are kids, they are dumb, all they know is they are innocent, they would never hurt anybody.I want to go up to them and say stop,

don’t do it—she’s the wrong woman,

he’s the wrong man, you are going to do things

you cannot imagine you would ever do,

you are going to do bad things to children,

you are going to suffer in ways you never heard of,

you are going to want to die. I want to go up to them there in the late may sunlight and say it[…]

but I don’t do it. I want to live. I take them up like the male and female

paper dolls and bang them together

at the hips, like chips of flint, as if to

strike sparks from them, I saydo what you are going to do, and I will tell about it.

Sharon Olds, I Go Back to May 1937 (1987)

thank you for reading ‘the years, retold’. the publication will remain free, and you’ll continue to have access to all the posts — for as long as you wish.

however, if you'd like to contribute with a small gift, you might want to consider a paid subscription…

….or support me through ko-fi (which is completely low commitment! you won’t be stuck to a monthly subscription and can just help whenever you feel like it): https://ko-fi.com/carolinabrasnovo

anyway, the most important thing is that you’re here. I’m very happy to have you.